Music 1 at OCA - Part II: Exploring Melodies and Scales

Revision of chapters 2, 4 and 11 of The AB Guide to Music Theory by Eric Taylor:

Introduction to Pitch

Semitones: Although infinite pitches are possible only 12 notes (12 semitones which is 7 notes and their accidentals) and their octave relates notes are played in practice.

Pitch: Depth or height of sound (low or high pitch).

Staff/Stave and Clef: Staff is the 5 lines where music notes are written. The Clef indicates the pitch represented in one of those lines then the rest if defined. Treble or G clef is most common (2 line is a G, guitar, right hand in piano). Bass Clef or F clef (F is 4th line) is used for left hand piano. If the clef changes between bar lines, the new one goes before the bar line.

· Extra lines can be added above or below called ledger lines. To avoid many ledger lines the sign 8 or 8va is used followed by continuous line.

· Note stems go up for notes below middle of staff and vice versa.

Sharps/flats/Naturals: Black notes in piano are sharps or flats of the white ones. Each has two names (e.g. A# or Bb, symbols are written before notes on the staff). The natural sign removes the sharp or flat quality of the note.

Intervals/semitones: the distance in pitch (interval) between any note and its nearest is 1 semitone/half tone which is raised by # and lowered by b.

Enharmonic: Two notes with the same sound but different name (C# and Db) although depending on the scale and/or function only 1 note name will be the correct.

Major Scale: Ascending or descending arrangement of a selected group of notes. C major scale is composed of C D E F G A B notes which are the 7 degrees of the scale (no accidentals). The formula of intervals between near notes is C-Tone-D-Tone-E-semitone-F-Tone-G-Tone-A-Tone-B-Semitone-C (TT S TTT S).

· G major Scale: 1 sharp is needed on F# to keep same formula [TT S TTT S]

G-Tone-A-Tone-B-Semitone-C-Tone-D-Tone-E-Tone-F#-Semitone-G

Key Signature (page 13): They are the accidentals needed to keep the same formula and is placed between Cleff and Time Signature. Key signature of G will be 1 sharp #. Key sig. of F major will be 1 b, etc. It’s written every line and if a change is needed, the new key sig. is placed after a double bar line.

Accidentals: Sharps, flats or naturals that do not belong to the key signature of that scale. If the same accidental appears too often, a key signature change may be needed. They remain in force until the end of the bar. No need to put the accidental again if the note in the new bar is tied to a previous accidental although the accidental will be needed if it appears again on that bar.

More Scales, Keys and Clefs

Circle of Fifths: Easy way to generate the circle of fifths quickly in order to know all the sharps and flats in all key signatures is the following:

- Start clockwise writing C at 12:00 and move down in fifths every “5 min” until F# at 6:00 (only sharp key signature).

- Anticlockwise, start from C and move on fourths down to F# but use a 3rd to go from Db to F# (it would be a 4th as well to go to Gb, enharmonic of F#). 5ths and 4ths are related.

- Clockwise (sharps), the key signatures will increase 1 # from C (0) to F# with 6#. The last sharp is always the 7th degree (e.g. G has 1 sharp which is A#) and we can go backwards all the sharps using 4ths (e.g. A has 3 sharps, the first one is its 7th degree G#, so all of them backwards are G#-C#(4th)-F#(4th)).

- Anticlockwise (flats) the key signatures will increase 1 b from C (0) to Db 5b). Note that key signature C# (7 #) or Db (5 b) are the same scales but we choose one for simplicity. The last b is always a 4th degree and we can go backwards all the flats using now 5ths! (Bb has 2 b, last one is Eb and previous is Bb (its fifth)).

Figure 2. Complete circle of fifths.

Natural Minor Scale: Relative A minor scale has the same notes as C major scale so the formula is now. A is the 6th degree of C. The formula for minor scale is now [A-Tone-B-Semitone-C-Tone-D-Tone-E-Semitone-F-Tone-G-Tone-A] [T S TT S TT]. This is the formula used to apply the key signature for minor scales. However, minor scales can be classified in 2:

o Melodic minor scale: As Natural for descending notes but sharpens 6th and 7th degree when ascending.

o Harmonic minor scale: Sharpens 7th degree in both ascending and descending ways.

Basically, we use Natural minor scale key signatures and any 6th and 7th degree can be sharpened but will need to be indicated in the score with accidentals.

The circle of fifths applies to the minor scales in the same way but now everything is rotated 6 degrees (e.g. D major has 2 sharps in the same way as B minor, B is 6th degree of D and B minor is said to be the relative minor of D major).

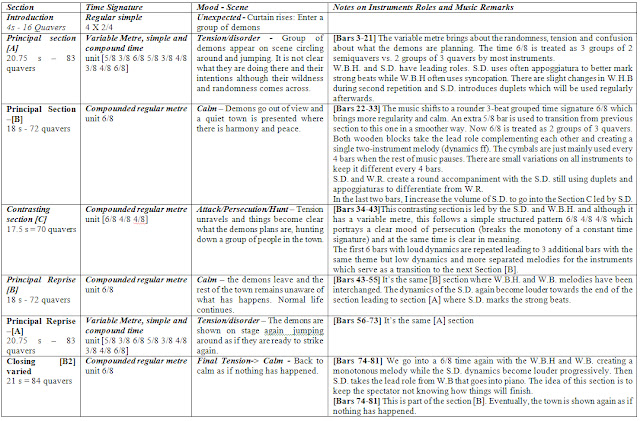

Table 1. Scale degree names and stability.

Double Sharps and double Flats: Scale of G# minor already has F# within so if we want to sharpen that F we cannot just put F# but Fx. Similarly with double flats but bb is used. To cancel then we just put 1 # or 1 b respectively.

Chromatic Scales (page 30): The scales of all major and minor keys are diatonic. Notes which do not belong to the scale are said to be chromatic (added “colour”). A chromatic scale is a scale made entirely of semitones. When chromatic notes are used too often within a diatonic scale, the feeling of tonality can be weakened.

C Clef: place on the 3rd or 4th line and indicates middle c.

Articulation

Generic Phrasing Marks: Often we can recognise phrases even without putting marks because of perfect cadences or repetition, etc. Phrasing marks do not only signal where phrases start and end but how notes are to be played (separated, rolled, bowing marks, etc).

Articulation marks:

- Slurs: Smooth play of notes (legato). It can cover a whole phrase or a portion of it. Brackets, middle strokes or dash lines indicate that it’s been included by editor. Last note in the slur is played shorter.

Figure 3. Notation of a Slur.

- In guitar we play this by doing ligados. A tie has the same symbol but joins two notes of same pitch. Sometimes, unconventional beaming is used to reinforce meaning of slurs (page 83).

- Slurs can contain other slurs to indicate that all the notes within the large slur belong to the same phrase or group.

- Staccato signs: shortening of a note. It doesn’t mean that the notes should be shortened as much as possible. If we combine the slur with staccato the notes will be shortened a bit less.

Figure 4. Staccato notation.

- Staccatissimo: short stroke. Shorten the note as much as possible.

Figure 5. Staccatissimo notation.

- Tenuto: Opposite to staccato and also indicates emphasis (horizontal dash is used) although there is still some separation compared to slurs.

Figure 6. Tenuto notation.

- Slurs, staccato and tenuto can be mixed.